The mechanisms of hearing are complex and our understanding of them is continually evolving. Simplified, the ear translates air movements into nerve impulses sent to the brain. These impulses are then further processed based on things like location to the listener, volume and quality to determine what’s “important” and what can be ignored.

The mechanisms of hearing are complex and our understanding of them is continually evolving. Simplified, the ear translates air movements into nerve impulses sent to the brain. These impulses are then further processed based on things like location to the listener, volume and quality to determine what’s “important” and what can be ignored.

The acoustics of hearing

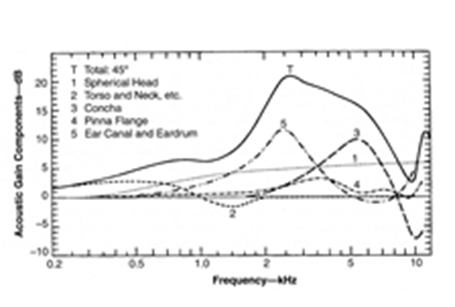

The intricate process of hearing begins with the ear canal and drum. That little opening in the side of your head has a surprisingly significant impact on how you hear. Like a subwoofer, the canal itself creates resonances which amplify or reduce specific frequencies. This is why even minor blockages can create problems with sound and speech recognition. Voice communications average around the 2000Hz range and the ear canal amplifies this peak. Changes in the shape of this acoustic chamber (as well as changes to the external ear) can alter the location of this peak, causing a distortion in sound.

Figure 1: Amplification in the ear canal

(Musiek, Frank E., Jane A. Baran. The Auditory System: Anatomy, Physiology, and Clinical Correlates. Allyn & Bacon. March 2006. Page 46)

The anatomy of hearing

After air vibrations reach the eardrum, delicate bones transcribe them to the fluid-filled chambers of the inner ear. Similar to tapping the skin of a water balloon, the sound ripples through the perilymph to a second fluid-filled chamber containing endolymph where things get really interesting.

Bathed within the endolymphatic chamber are the hair cells. These marvels of evolution translate fluid vibrations into nerve impulses that get carried to the brain. These hair cells are evolutionally related to neurons, and function in much the same way. The vibration causes change in the intracellular (inside the cell) potassium and calcium levels, releasing neurotransmitters that stimulate electro-chemical impulses down the hearing nerves.

The psychoacoustics of hearing

These afferent (to the brain) nerves carry impulses through the brainstem to the “auditory belt” which decides which signals are important. The “important” signals continue on to the cortices of the brain and our conscious hearing while others – don’t. This is one reason we can locate sound and “tune-out” background noise like ignoring someone else’s conversation at a party. As a part of this process, the brain also sends impulses back to the ear (efferent impulses) which change how the hair cells respond to sound by physically changing their shape and how they respond to ions.

How does anatomy affect tinnitus?

Considering this elaborate chain of events, it’s easy to see how a hiccup at any point could create noise. It’s also why tinnitus can be so difficult to treat effectively. When an obvious link in the chain is disrupted, for example with acoustic neuroma, the targeting of treatment is relatively straightforward. When it’s more idiopathic (unknown) things become challenging. Research into both the hearing mechanisms and treatments for tinnitus continue. Every day new and amazing discoveries are made although it will be some time before the mysteries of the ear, hearing and balance fully unravel.